Kevin Warwick

| Kevin Warwick | |

|---|---|

Kevin Warwick, February 2008

|

|

| Born | 9 February 1954 Coventry, UK |

| Nationality | |

| Fields | Cybernetics, robotics |

| Institutions | University of Oxford Newcastle University University of Warwick University of Reading |

| Alma mater | Aston University Imperial College London |

| Doctoral advisor | John Hugh Westcott |

| Doctoral students | Mark Gasson |

| Known for | Project Cyborg |

Kevin Warwick (born 9 February 1954 Coventry, UK) is a British scientist and professor of cybernetics at the University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire, United Kingdom. He is best known for his studies on direct interfaces between computer systems and the human nervous system, although he has also done much research in the field of robotics.

Contents |

Biography

Kevin Warwick was born in 1954 in Coventry in the United Kingdom. He attended Lawrence Sheriff School in Rugby, Warwickshire. He left school in 1970 to join British Telecom, at the age of 16. In 1976 he took his first degree at Aston University, followed by a Ph.D and a research post at Imperial College London.

He subsequently held positions at Oxford, Newcastle and Warwick universities before being offered the Chair in Cybernetics at the University of Reading in 1987.

Warwick is a Chartered Engineer, a Fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology and a Fellow of the City and Guilds of London Institute. He is Visiting Professor at the Czech Technical University in Prague and in 2004 was Senior Beckman Fellow at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA. He is also Director of the University of Reading Knowledge Transfer Partnerships Centre, which links the University with Companies and is on the Advisory Board of the Instinctive Computing Laboratory, Carnegie Mellon University.[1] He has been awarded higher doctorates (D.Sc.) by Imperial College and by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Prague.

Work

Warwick carries out research in artificial intelligence, biomedical engineering, control systems and robotics. Much of Warwick's early research was in the area of discrete time adaptive control. He introduced the first state space based self-tuning controller[2] and unified discrete time state space representations of ARMA models.[3] However he also contributed in mathematics,[4] power engineering[5] and manufacturing production machinery.[6]

Artificial intelligence

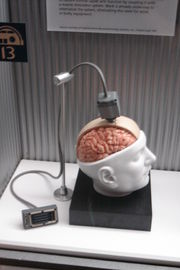

Warwick presently heads an Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council supported research project which investigates the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence techniques in order to suitably stimulate and translate patterns of electrical activity from living cultured neural networks in order to utilise the networks for the control of mobile robots.[7] Hence a biological brain actually provides the behaviour process for each robot. It is expected that the method will be extended to the control of a robot head.

Previously Warwick was behind a Genetic algorithm called Gershwyn, which was able to exhibit creativity in producing pop songs, learning what makes a hit record by listening to examples of previous hit songs.[8] Gershwyn appeared on BBC's Tomorrow's World having been successfully used to mix music for Manus, a group consisting of the four younger brothers of Elvis Costello.

Another Warwick project involving artificial intelligence is the robot head, Morgui. The head contains 5 senses (vision, sound, infrared, ultrasound and radar) and is being used to investigate sensor data fusion. The head was X-rated by the University of Reading Research and Ethics Committee due to its image storage capabilities - anyone under the age of 18 who wishes to interact with the robot must apriori obtain parental approval.[9]

Warwick has very outspoken views on the future, particularly with respect to artificial intelligence and its impact on the human species, and argues that we will need to use technology to enhance ourselves in order to avoid being overtaken. He also points out that there are many limits, such as our sensorimotor abilities, that we can overcome with machines, and is on record as saying that he wants to gain these abilities: "There is no way I want to stay a mere human."[10]

Bioethics

Warwick heads the University of Reading team in a number of European Community projects such as FIDIS looking at issues concerned with the future of identity and ETHICBOTS which is considering the ethical aspects of robots and cyborgs. Warwick is also working with Daniela Cerqui, a social and cultural anthropologist from the University of Lausanne, to address the main social, ethical, philosophical and anthropological issues related to his research.[11]

Warwick’s areas of interest have many ethical implications, some due to his Human enhancement experiments. The ethical dilemmas in his research are highlighted as a case study for schoolchildren and science teachers by the Institute of Physics[12] as a part of their formal Advanced level and GCSE studies. His work has also been directly discussed by The President's Council on Bioethics and the President’s Panel on Forward Engagements.[13]

Deep brain stimulation

Along with Tipu Aziz and his team at John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, and John Stein of the University of Oxford, Warwick is helping to design the next generation of Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease.[14] Instead of stimulating the brain all the time, the aim is for the device to predict when stimulation is needed and to apply the signals prior to any tremors occurring to stop them before they even start[15].

Public awareness

Warwick has headed a number of projects aimed at exciting schoolchildren about the technology with which he is involved. In 2000 he received the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Millennium Award for his Schools Robot League. Meanwhile in 2007, 16 school teams were involved in designing a humanoid robot to dance and then complete an assault course—a final competition being held at the Science Museum (London). The project, entitled 'Androids Advance' was supported by EPSRC and was presented as an evening news item on Chinese television.[16]

Warwick contributes significantly to the public understanding of science by giving regular public lectures, taking part in radio programmes and through popular writing. He has appeared in numerous television documentary programmes on artificial intelligence, robotics and the role of science fiction in science, such as How William Shatner Changed the World, Future Fantastic and Explorations.[17] He has also guested on a number of TV chat shows, including Late Night with Conan O'Brien, Først & sist, and Richard & Judy.[17] Warwick has appeared on the cover of a number of magazines, for example the February 2000 edition of Wired.[18]

In 2005 he was congratulated for his work in attracting students to the field by Members of Parliament in the United Kingdom in an Early day motion for making "the subject interesting and relevant so that more students will want to develop a career in science".[19]

Robotics

Warwick's claims that robots that can program themselves to avoid each other while operating in a group raise the issue of self-organisation, and as such might be the major impetus in following developments in this area. In particular, the works of Francisco Varela and Humberto Maturana, once in the province of pure speculation now have become immediately relevant with respect to synthetic intelligence.

Cyborg-type systems not only are homeostatic (meaning that they are able to preserve stable internal conditions in various environments) but adaptive, if they are to survive. Testing the claims of Varela and Maturana via synthetic devices is the larger and more serious concern in the discussion about Warwick and those involved in similar research. "Pulling the plug" on independent devices cannot be as simple as it appears, for if the device displays sufficient intelligence and assumes a diagnostic and prognostic stature, we may ultimately one day be forced to decide between what it could be telling us as counterintuitive (but correct) and our impulse to disconnect because of our limited and "intuitive" perceptions.

Warwick's robots seemed to have exhibited behaviour not anticipated by the research, one such robot "committing suicide" because it could not cope with its environment.[20] In a more complex setting, it may be asked whether a "natural selection" may be possible, neural networks being the major operative.

The 1999 edition of the Guinness Book of Records recorded that Warwick carried out the first robot learning experiment across the internet. One robot, with an Artificial Neural Network brain in Reading, UK, learnt how to move around. It then taught, via the internet, another robot in SUNY Buffalo New York State, USA, to behave in the same way. The robot in the USA was therefore not taught or programmed by a human, but rather by another robot based on what it itself had learnt.[21]

Hissing Sid was a robot cat which Warwick took on a British Council lecture tour of Russia, it being presented in lectures at such places as Moscow State University. Sid, which was put together as a student project, got its name from the noise made by the Pneumatic actuators used to drive its legs when walking. The robot also appeared on BBC TV's Blue Peter but became better known when it was refused a ticket by British Airways on the grounds that they did not allow animals in the cabin.[22]

Warwick was also responsible for a robotic "magic chair" which Sir Jimmy Savile used on BBC TV's Jim'll Fix It. The chair provided Jim with tea and stored Jim'll Fix it badges for him to hand out to guests.[23] Warwick even appeared on the programme himself for a Fix it involving robots.[17]

Project Cyborg

Probably the most famous piece of research undertaken by Warwick (and the origin of the nickname, "Captain Cyborg", given to him by The Register) is the set of experiments known as Project Cyborg, in which he had a chip implanted into his arm, with the aim of "becoming a cyborg".

The first stage of this research, which began on 24 May 1998, involved a simple RFID transmitter being implanted beneath Warwick's skin, and used to control doors, lights, heaters, and other computer-controlled devices based on his proximity. The main purpose of this experiment was said to be to test the limits of what the body would accept, and how easy it would be to receive a meaningful signal from the chip.[24]

The second stage involved a more complex neural interface which was designed and built especially for the experiment by Dr. Mark Gasson and his team at the University of Reading. This device consisted of an internal electrode array, connected to an external "gauntlet" that housed supporting electronics. was implanted on 14 March 2002, and interfaced directly into Warwick's nervous system. The electrode array inserted contained 100 electrodes, of which 25 could be accessed at any one time, whereas the median nerve which it monitored carries many times that number of signals. The experiment proved successful, and the signal produced was detailed enough that a robot arm developed by Warwick's colleague, Dr Peter Kyberd, was able to mimic the actions of Warwick's own arm.[25]

By means of the implant, Warwick's nervous system was connected onto the internet in Columbia University, New York. From there he was able to control the robot arm in the University of Reading and to obtain feedback from sensors in the finger tips. He also successfully connected ultrasonic sensors on a baseball cap and experienced a form of extra sensory input.[26]

A highly publicised extension to the experiment, in which a simpler array was implanted into the arm of Warwick's wife—with the aim of creating a form of telepathy or empathy using the Internet to communicate the signal from afar—was also successful, resulting in the first purely electronic communication experiment between the nervous systems of two humans.[27] Finally, the effect of the implant on Warwick's hand function was measured using the University of Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure (SHAP).[28] It was feared that directly interfacing with the nervous system might cause some form of damage or interference, but no measurable effect nor rejection was found. Indeed, nerve tissue was seen to grow around the electrode array, enclosing the sensor[29]

As well as the Project Cyborg work, Warwick has been involved in several of the major robotics developments within the Cybernetics Department at Reading. These include the "seven dwarves", a version of which was given away in kit form as Cybot on the cover of Real Robots Magazine.

Implications and criticisms on Project Cyborg

Warwick and his colleagues claim that the Project Cyborg research could lead to new medical tools for treating patients with damage to the nervous system, as well as opening the way for the more ambitious enhancements Warwick advocates. Some transhumanists even speculate that similar technologies could be used for technology-facilitated telepathy."[30] Warwick himself asserts that his controversial work is important because it directly tests the boundaries of what is known about the human ability to integrate with computerised systems.

A controversy arose in August 2002, shortly after the Soham murders, when Warwick reportedly offered to implant a tracking device into an 11-year-old girl as an anti-abduction measure. The plan produced a mixed reaction, with support from many worried parents but ethical concerns from a number of children's societies. As a result, the idea did not go ahead.

Anti-theft RFID chips are common in jewelry or clothing in some Latin American countries due to a high abduction rate,[31] and the company VeriChip announced plans in 2001 to expand its line of currently available medical information implants,[32] to be GPS trackable when combined with a separate GPS device.[33][34]

Turing Interrogator

Warwick has participated as a Turing Interrogator, on two occasions, judging machines in the 2001 and 2006 Loebner Prize competitions, platforms for an 'imitation game' as devised by Alan Turing. The 2001 Prize, held at the Science Museum in London, featured Turing's 'jury service' or one-to-one Turing tests and was won by A.L.I.C.E.[35] The 2006 contest staged parallel-paired Turing tests at University College London and was won by Rollo Carpenter. Kevin's findings can be found in a number of articles with co-author Huma Shah including Turing Test: Mindless Game? – A Reflection on the Loebner Prize - a paper presented at the 2007 European conference on computing and philosophy (ECAP),[36] and Emotion in the Turing Test - a chapter in a new Handbook on Synthetic Emotions and Sociable Robotics: New Applications in Affective Computing and Artificial Intelligence.[37] He organised the 2008 Loebner Prize at the University of Reading; a report on the contest's 'theatre of two Turing tests' can be found here.[38]

Other

Warwick was a member of the 2001 Higher Education Funding Council for England (unit 29) Research Assessment Exercise panel on Electrical and Electronic Engineering and was Deputy Chairman for the same panel (unit 24) in 2008.[39] He also sits on the research committee of The Guide Dogs for the Blind Association. In March 2009, he was cited as being the inspiration of National Young Scientist of the Year, Peter Hatfield

Awards and recognition

Warwick was presented with The Future of Health Technology Award from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was made an Honorary Member of the Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, was awarded the University of Malta medal from the Edward de Bono Institute and in 2004 received The Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE) Senior Achievement Medal.[40]

In 2008 Warwick was awarded the Mountbatten Medal[41] and received Honorary Doctor of Science degrees in 2008 from Aston University[42] and Coventry University[43] and in 2010 from Bradford University[44]. In 2009 he received the Marcellin Champagnat award from Universidad Marista Guadalajara and the Golden Eurydice Award[45]

Quotations

- “Shouldn’t I join the ranks of philosophers and merely make unsubstantiated claims about the wonders of human consciousness? Shouldn’t I stop trying to do some science and keep my head down? Indeed not”.[46]

- “I feel that we are all philosophers, and that those who describe themselves as a ‘philosopher’ simply do not have a day job to go to”.[46]

- On Human Consciousness: “John Searle put forward the view that a shoe is not conscious therefore a computer cannot be conscious. By the same sort of analogy though, a cabbage is not conscious therefore a human cannot be conscious”.[47]

- On Machine Intelligence: “Our robots have roughly the equivalent of 50 to 100 brain cells. That means they are about as intelligent as a slug or snail or a Manchester United supporter”.[47]

- “An actual robot walking machine which takes one step and then falls over is worth far more than a computer simulation of 29,000 robots running the London Marathon in record time”.[47]

- “When comparing human memory and computer memory it is clear that the human version has two distinct disadvantages. Firstly, as indeed I have experienced myself, due to ageing, human memory can exhibit very poor short term recall”.[47]

- "There can be no absolute reality, there can be no absolute truth".[48]

- "Ask not what the surgeon can do for you - ask what you can do for the surgeon", Panel Discussion on Challenges & Opportunities in Biomedical Engineering at BIOSTEC 2008 Conference, Madeira, Portugal, 28 January 2008.

Trivia

Warwick's Erdős–Bacon number is 6: he co-authored a number of scholarly articles with Yakov Tsypkin,[49] who has an Erdős number of 3 and has appeared in several documentaries alongside people who have a Bacon number of 1, examples being Laurence Fishburne, William Shatner and Steven Spielberg.[50]

See also

- God helmet

- Ray Kurzweil and The Age of Intelligent Machines

- Stelarc

- Steve Mann

- Transhumanism

- Who's Who

Publications

Warwick has written several books, articles and papers. A selection of his books:

- Warwick, Kevin (2001). QI: The Quest for Intelligence. Piatkus Books. ISBN 0749922303.

- Warwick, Kevin (2004). I, Cyborg. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252072154.

- Warwick, Kevin (2004). March of the Machines: The Breakthrough in Artificial Intelligence. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252072235.

Lectures (inaugural and keynote lectures):

- 1998, Robert Boyle Lecture at Oxford University,

- 2000, “The Rise of The Robots”, Royal Institution Christmas Lectures. These lectures were repeated in 2001 in a tour of Japan, China and Korea.

- 2001, Gordon Higginson Lecture at Durham University, Hamilton institute inaugural lecture.

- 2003, Royal Academy of Engineering/Royal Society of Edinburgh Joint lecture in Edinburgh,

- 2003, IEEE (UK) Annual Lecture in London; Pittsburgh International Science and Technology Festival.[51]

- 2004, Woolmer Lecture at University of York; Robert Hooke Lecture (Westminster)

- 2005, Einstein Lecture in Potsdam, Germany

- 2006, Bernard Price Lecture tour in South Africa; Institution of Mechanical Engineers Prestige Lecture in London.

- 2007, Techfest plenary lecture in Mumbai; Kshitij keynote in Kharagpur (India); Engineer Techfest plenary lecture in NITK Surathkal (India); Annual Science Faculty lecture at University of Leicester; Graduate School in Physical Sciences and Engineering Annual Lecture, Cardiff University.

- 2008, Leslie Oliver Oration[52] at Queen's Hospital; Techkriti keynote in Kanpur.

- 2008, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, guest lecture "Four weddings and a Funeral" for the Microsoft Research Chair.

- 2009, Cardiff University, 125th Anniversary Lecture; Orwell Society, Eton College.[53]

- 2010, Robert Gordon University launch of Research Institute for Innovation Design and Sustainability (IDEAS)[54]

He is a regular presenter at the annual Careers Scotland Space School, University of Strathclyde.

He appeared at the 2009 World Science Festival[55] with Mary McDonnell, Nick Bostrom, Faith Salie and Hod Lipson.

References

- ↑ "Ambient Intelligence Lab (AIL) - Ambient Intelligence". Cmu.edu. http://www.cmu.edu/vis/. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ Kevin, Warwick (1981). "Self-tuning regulators: A state-space approach". International Journal of Control 33 (5): 839–858. doi:10.1080/00207178108922958.

- ↑ Warwick, K: "Relationship between Åström control and the Kalman linear regulator - Caines revisited", Journal of Optimal Control:Applications and Methods, 11(3), pp.223-232, 1990

- ↑ Warwick,K:"Using the Cayley–Hamilton theorem with N partitioned matrices",IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, AC.28(12),pp.1127-1128, 1983

- ↑ Warwick, K, Ekwue, A and Aggarwal, R (eds). "Artificial intelligence techniques in power systems", Institution of Electrical Engineers Press, 1997

- ↑ Sutanto, E and Warwick, K: "Multivariable cluster analysis for high speed industrial machinery", IEE Proceedings - Science, Measurement and Technology, 142, pp. 417-423, 1995

- ↑ "Rise of the rat-brained robots - tech - 13 August 2008 - New Scientist". Technology.newscientist.com. http://technology.newscientist.com/channel/tech/mg19926696.100-rise-of-the-ratbrained-robots.html. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ BBC News | Entertainment | To the beat of the byte

- ↑ Radford, Tim (2003-07-13). "University robot ruled too scary". The Guardian (London: Guardian Media Group). http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2003/jul/17/highereducation.science.

- ↑ Kevin Warwick, FAQ, http://www.kevinwarwick.com/faq.htm (last question)

- ↑ www.kevinwarwick.com

- ↑ PEEP Physics Ethics Education Project: People

- ↑ Introduction

- ↑ HuntGrubbe, Charlotte (2007-07-22). "The blade runner generation". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article2079637.ece. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Wu,D., Warwick, K., Ma, Z., Burgess, J., Pan, S. and Aziz, T: “Prediction of Parkinson’s disease tremor onset using radial basis function neural networks”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol.37, Issue.4, pp.2923-2928, 2010

- ↑ 英国类人机器人大赛 寓教于乐两相宜(机器人,教育,科技,发展,英国 ) - 新视界-全球资讯视频总汇

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kevin Warwick

- ↑ Cover Browser - Wired Magazine

- ↑ www.edms.org.uk/edms/2004-2005/964.xml

- ↑ Warwick, K: “I, Cyborg”, University of Illinois Press, 2004, p 66

- ↑ Warwick, K: “I, Cyborg”, University of Illinois Press, 2004

- ↑ "-BA criticised over denying boarding to robotic cat". Airline Industry Information. 1999-10-22. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0CWU/is_/ai_56752397.

- ↑ Delaney, Sam (2007-03-31). "Now then, now then". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/theguide/tvradio/story/0,,2045929,00.html. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ↑ Wired Magazine 8.02 (February 2000), 'Cyborg 1.0: Interview with Kevin Warwick', http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/8.02/warwick.html . Retrieved 25-12-2006.

- ↑ Warwick, K, Gasson, M, Hutt, B, Goodhew, I, Kyberd, P, Andrews, B, Teddy, P and Shad, A:“The Application of Implant Technology for Cybernetic Systems”, Archives of Neurology, 60(10), pp1369-1373, 2003

- ↑ Warwick, K, Hutt, B, Gasson, M and Goodhew, I:“An attempt to extend human sensory capabilities by means of implant technology”, Proceedings IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Hawaii, pp.1663-1668, October 2005

- ↑ Warwick, K, Gasson, M, Hutt, B, Goodhew, I, Kyberd, P, Schulzrinne, H and Wu, X: “Thought Communication and Control: A First Step using Radiotelegraphy”, IEE Proceedings on Communications, 151(3), pp.185-189, 2004

- ↑ Kyberd, P, Murgia, A, Gasson, M, Tjerks, T, Metcalf, C, Chappell, P, Warwick, K, Lawson, S and Barnhill, T: "Case studies to demonstrate the range of applications of the Southampton Hand Assessment Procedure", British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(5), pp.212-218, 2009

- ↑ Gasson, M.N., Hutt, B.D., Goodhew, I., Kyberd, P., and Warwick, K: "Invasive Neural Prosthesis for Neural Signal Detection and Nerve Stimulation", International Journal of Adaptive Control and Signal Processing, Vol.19:5, pp.365-75, 2005.

- ↑ George Dvorsky (2004-04-26). "Evolving Towards Telepathy". Betterhumans. Archived from the original on 2007-07-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20070706064752/http://archives.betterhumans.com/Columns/Column/tabid/79/Column/267/Default.aspx.

- ↑ missingbyline (missingdateline). "missingtitle". Arizona Daily Star. http://www.dailystar.com/dailystar/news/30069.php.

- ↑ VeriChip. "Implantable Verification Solution for SE Asia". Inforlexus. http://www.verichip.com.my/index-2.html.

- ↑ Julia Scheeres (2002-01-25). "Kidnapped? GPS to the Rescue". Wired News. http://www.wired.com/news/business/0,1367,50004,00.html.

- ↑ Julia Scheeres (2002-02-15). "Politician Wants to 'Get Chipped'". Wired News. http://www.wired.com/news/technology/0,1282,50435,00.html.

- ↑ The A. L. I. C. E. Artificial Intelligence Foundation - chatbot - chat bot - chatterbots - verbots - natural language - chatterbot - bot - chat robot - chat bots - AIML - take a Turing Test - Loebner ...

- ↑ European Computing and Philosophy Conference

- ↑ Handbook of Research on Synthetic Emotions and Sociable Robotics: New Applications in Affective Computing and Artificial Intelligence, IGI Global

- ↑ "Can a machine think? - results from the 18th Loebner Prize contest - University of Reading". Rdg.ac.uk. http://www.rdg.ac.uk/research/Highlights-News/featuresnews/res-featureloebner.asp. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.rae.ac.uk/ Current official RAE website for 2008 exercise

- ↑ http://www.theiet.org/about/scholarships-awards/achievement/medals-what.cfm

- ↑ Media-Newswire.com - Press Release Distribution (2008-11-20). "Press Release Distribution - PR Agency". Media-Newswire.com. http://media-newswire.com/release_1079897.html. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ High profile graduates celebrated by Aston University

- ↑ "Honorary degree delight for outstanding individuals at Coventry University". Coventry.ac.uk. http://www.coventry.ac.uk/latestnewsandevents/a/4879. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.brad.ac.uk/mediacentre/press-releases/Title_27186_en.php

- ↑ http://www.ictthatmakesthedifference.eu/2009.1122.programme/

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Hendricks, V: “Feisty Fragments for Philosophy”, King’s College Publications, London,2004.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Hendricks, V: “500 CC Computer Citations”, King’s College Publications, London, 2005

- ↑ Warwick, K:"The Matrix - Our Future?", Chapter in "Philosophers Explore the Matrix", edited by C.Grau, Oxford University Press, 2005

- ↑ Tsypkin, Ya. Z, Parks, P, Vishnyakov, A and Warwick, K:"Stability of Solutions of Linear Difference Equations with Periodic Coefficients", International Journal of Control, 64(5), pp959-966, 1996

- ↑ "The Oracle of Bacon". The Oracle of Bacon. http://oracleofbacon.org/cgi-bin/movielinks. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.scitechfestival.com/2004/AR2003.pdf

- ↑ BHR University Hospitals. "Inaugural Leslie Oliver Oration". Bhrhospitals.nhs.uk. http://www.bhrhospitals.nhs.uk/neuro/neuro4ha.php?id=964. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ "Events". Kevinwarwick.com. http://www.kevinwarwick.com/events.asp?Date=15%2F9%2F2009. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

- ↑ http://www.rgu.ac.uk/events/launch-of-ideas

- ↑ "Battlestar Galactica Cyborgs on the Horizon". World Science Festival. 2009-06-12. http://www.worldsciencefestival.com/2009/battlestar-galactica. Retrieved 2009-09-26.

External links

- Kevin Warwick's official site

- RTE Radio 1 debate with Kevin Warwick on Human Enhancement [podcast link http://www.rte.ie/radio1/podcast/podcast_sciencedebate.xml]

- Ananova story, with pictures of the chip and operation (dead link, see archive)

- IET Robotics Network

- List of articles mentioning "Captain Cyborg" at the Register

- Kevin Warwick at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Kevin Warwick at the Internet Movie Database

- Interview with Kevin Warwick in The Future Fire 1 (2005)

- Video of Kevin Warwick speaking at WhatTheHack

- Interview with Kevin Warwick in mbr:points 1 (04.02.2008)

- Interview with Kevin Warwick on cyborgs, viruses, Cyborg Rights and cyborg-identity (1 December 2008)

- Interview with Kevin Warwick in IT-BHU Chronicle

- http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=self-experimenters on-line Scientific American article

- Kevin Warwick at LIFT 08

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||